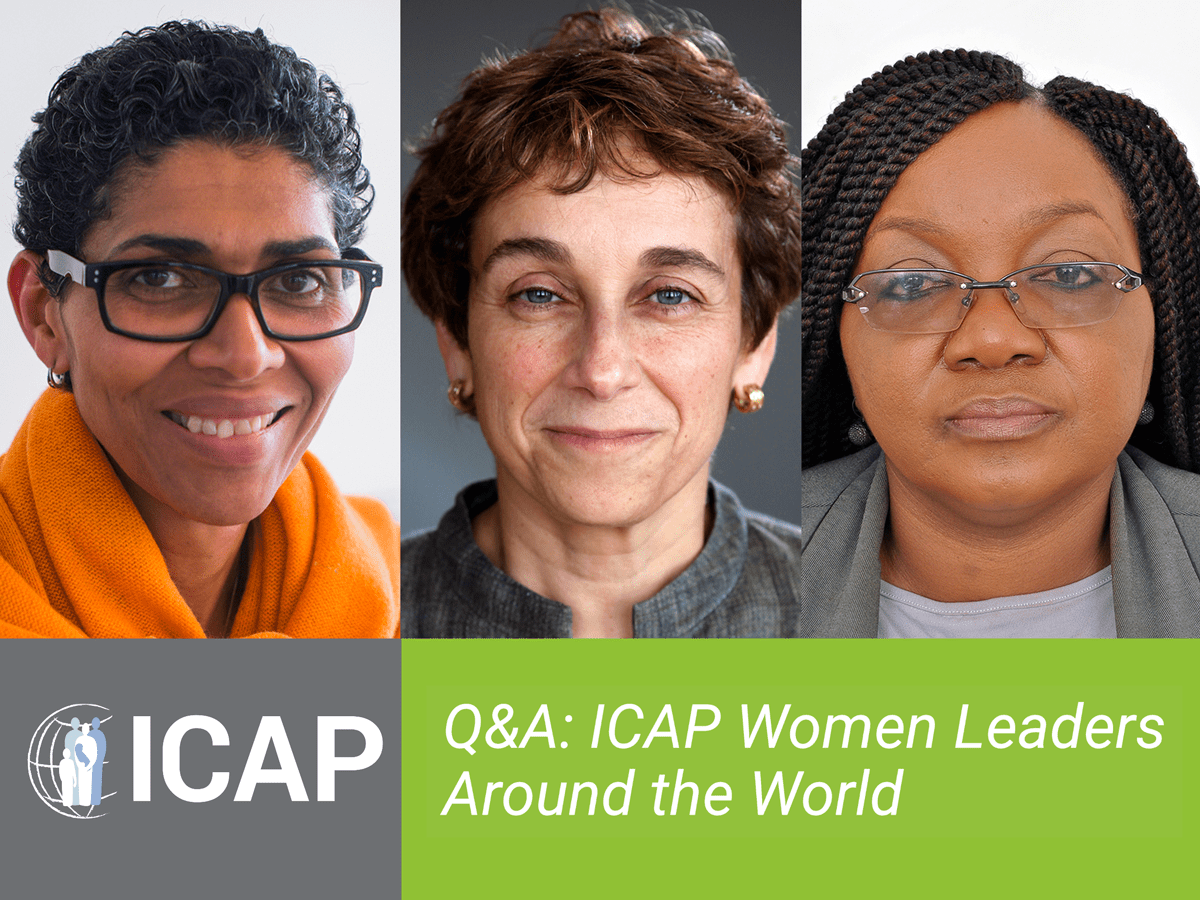

At the helm of ICAP’s innovative programs and projects, a group of women experts are playing leadership roles in global health. ICAP’s women leaders develop and lead complex implementation projects for HIV prevention, care, and treatment; build the capacity of health workers; perform cutting-edge research; coordinate monitoring and reporting systems; and strengthen health systems in the world’s most challenging settings.

In this second edition of our women leaders Q&A series, we feature three accomplished women who worked through a time when society often overlooked the health care needs of women, and when female doctors had to strive for recognition in their professional fields. With more than 60 years of combined work experience among the three of them, these women leaders share their perspectives on how women can overcome challenges in an often male-dominated health care sector.

Elaine Abrams, MD, is ICAP’s senior research director and a professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Columbia University. She is also responsible for a growing list of operational research studies of HIV prevention, care, and treatment programs.

Prisca Kasonde, MD, MMed, MPH, is the country director for ICAP in Zambia. Kasonde is a physician and public health specialist with more than 24 years of clinical and program management experience in the areas of HIV/AIDS, STIs, reproductive health, obstetrics and gynecology, and health systems strengthening.

Stéphania Koblavi Dème, PharmD, PhD, is ICAP’s country director in Côte d’Ivoire. She has over 20 years of experience as a laboratory specialist.

Q: Being a woman is often framed as a disadvantage, but are there times or circumstances where it has been an advantage, especially within the public health sector?

PK: I have never felt disadvantaged as a woman in my whole work life. Of course, I have had instances, very early in my career, where others, including patients, thought that because I am female, I am a nurse, and the male nurse working with me is the doctor. However, when I served in some of the peri-urban and rural areas during my practice, some female patients and their families had reservations about getting checkups from male doctors, especially gynecological checks. Being a woman worked to my advantage as the patients were able to open up more to me as a female doctor.

EA: I think the most significant advantage of being a woman in this field is that there is a better understanding of many of the critical public health issues that affect women and children. As a woman, you come at those issues with a different eye and an ethos that may elevate the importance of those issues, populations, and provide a little bit more energy to specifically focusing on public health issues that affect women and children. That has been the driver in the work that we do at ICAP.

SKD: I believe women are more empathetic to patients and have a slightly different approach to health care than male doctors, which becomes an advantage when implementing health sector programs.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve received as a career woman?

SKD: Always use your results, and your work to make your point, and express your ideas. Also, never try to hide that you don’t have the answer to something – ask for support.

PK: When I was training to be an OBGYN specialist at the University Teaching hospital in Lusaka, there was a reputation in the department that exams there were for ‘failing,’ and you needed to impress the supervisors to pass after the second, third or even fourth attempt. However, there was an elderly male professor who was one of my supervisors. I think he saw my potential and work ethic said to me, “you are a great doctor and postgraduate student if you remain as focused as you are now, you will go far. It doesn’t matter that you are a woman.”

EA: I don’t know whether this advice is specific to being a career woman, but you have to believe what you’re doing is important and be passionate about it. Make choices about what you’re going to do, where you’re going to focus your time, energy, and it has to be important to you. That has been a guiding principle for me, and also what I often say to young people as they are starting their career.

Q: What advice would you give to young women looking to work in the health care sector?

PK: I usually tell other women in the health care sector not to have a laissez-faire attitude – work hard, and everything else will fall into place.

SKD: Knowledge brings you respect. There is no need to brood over the challenges of being a woman in the health care sector because more and more of society is accepting that our differences are just important facts for natural diversity and different ways of implementing actions.

Q: What are your aspirations for the women of the next generation?

EA: I hope young women of the next generation don’t stop asking the question, “how would a man be treated in this position, and am I being treated differently?” When I’m working with young women who are making career decisions, I often say to them, “how much are the men making? What are the expectations for a man in this position, and are they different for you? Are you holding yourself to a different standard or set of rules?” I hope that at some point all of that goes away.

PK: My hope is for young women to excel in whatever profession they undertake; they need to be assertive, proactive in their work, and results-oriented.

SKD: I hope the growing social equity between men and women means women of the next generation have the same freedoms men have without the additional burden of gender.

A global health leader since 2003, ICAP was founded at Columbia University with one overarching goal: to improve the health of families and communities. Together with its partners—ministries of health, large multilaterals, health care providers, and patients—ICAP strives for a world where health is available to all. To date, ICAP has addressed major public health challenges and the needs of local health systems through 6,000 sites across more than 30 countries.