In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly declared February 11 the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

International Day of Women and Girls in Science recognizes the important role women and girls play in science and technology, but also aims to highlight the major obstacles women often face when pursuing interests and careers in science. Women make up only 30 percent of the world’s researchers. Even though most of the world’s health care workforce is comprised of women, only about a third are doctors. Women also continue to occupy significantly fewer senior positions than men at top universities.

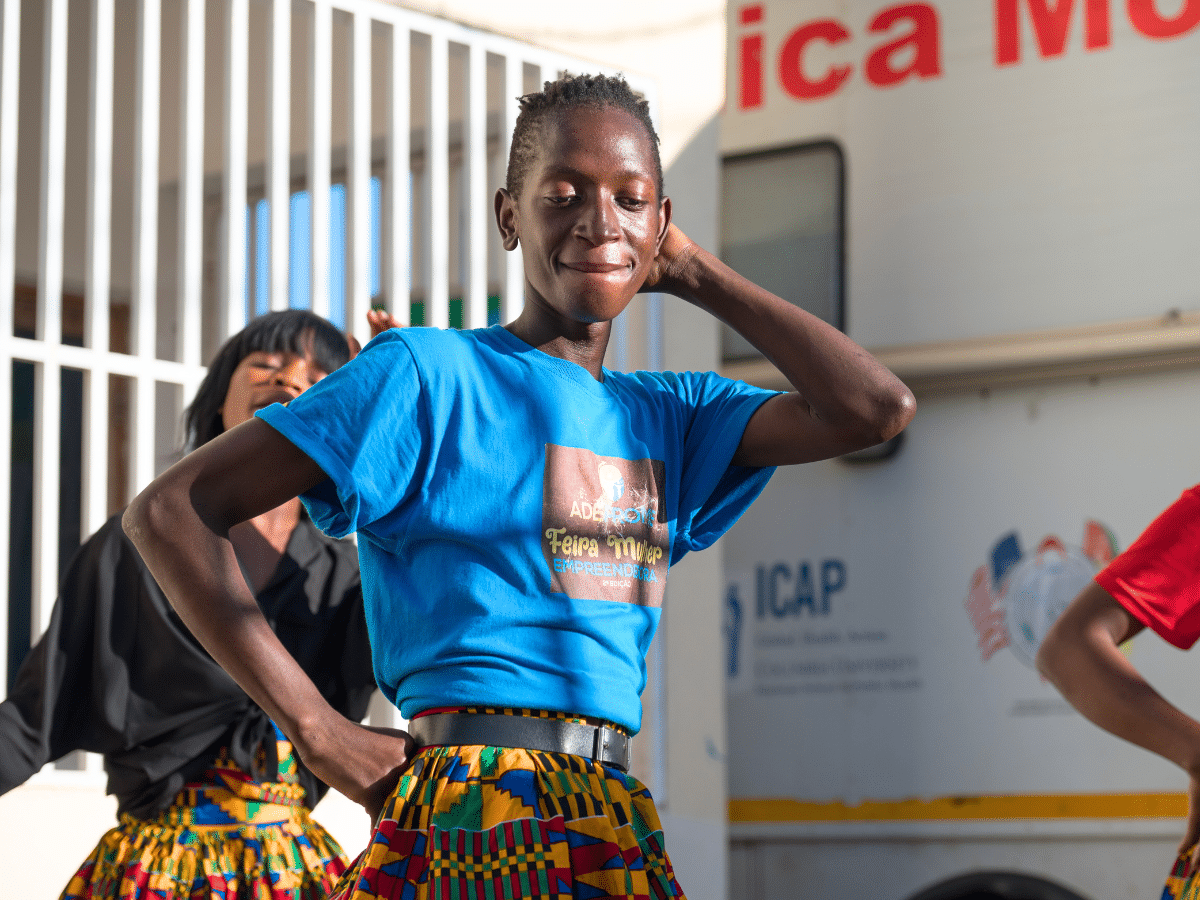

Standing apart from the status quo, ICAP at Columbia University is led by numerous women researchers, scientists, and public health experts who shape policy, manage major global health projects, and contribute to health innovations.

Thanks to the vision of its women leaders, ICAP frequently develops and implements initiatives that serve and address women’s health issues, which are often neglected in many parts of the world. In South Africa, for example, ICAP researchers examined the effects of adverse childhood experiences on maternal psychosocial and HIV-related outcomes. In Eswatini, an ICAP-supported clinical study assessed the effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in preventing HIV acquisition in women.

As the International Day of Women and Girls in Science commences, ICAP recognizes some of the women leading global health conversations at ICAP, the research they spearhead, and the path they hope to pave for those who follow in their footsteps.

Julie Franks, PhD, is a senior technical specialist at ICAP focusing on HIV testing and prevention, particularly among key populations heavily impacted by HIV.

Susan Michaels-Strasser, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN, is the senior director of Human Resources for Health at ICAP, helping to improve acute and chronic health care as well as management and mitigation of disease outbreaks throughout the organization’s projects.

Andrea Low, MSc, PhD, is assistant professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health and a senior technical advisor collaborating on the CQUIN and PHIA projects at ICAP, which both focus on HIV.

Andrea Howard, MD, MS, is director of the Clinical and Training unit at ICAP, overseeing the design and implementation of ICAP’s clinical, laboratory, and training programs for the prevention, care and treatment of HIV, tuberculosis, and other conditions of public health significance.

Q: What contributions have you have made to science thus far that you are most proud of?

JF: The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) Study 061 was the largest longitudinal research cohort of black men who have sex with men in the U.S. and was also led by black and gay scientists. Findings from the study reshaped HIV prevention in the U.S. and 10+ years later still contributes to advancing the visibility of black and gender- and sexual minority American health needs.

Additionally, in the spring of 2020, when NYC and the world still had no effective tools against COVID-19, we heard the early HPTN 083 results showing that long-acting injectable PrEP was more effective than daily oral PrEP at preventing HIV disease. It was a humbling moment to be on the call hearing the results of a study co-led by prominent women in the field. It was important that results of 083 came in the early part of the pandemic because it was a reminder that scientists and people vulnerable to devastating viruses can work together to create effective tools against disease. We would see further proof of that within a year in effective vaccines and then treatment against COVID-19. We really needed the reminder in the spring of 2020!

SMS: Research that has led to national policy change in sub-Saharan Africa. I served as lead investigator in Zambia on a multi-country study to address perinatal transmission of syphilis. This study was done as a collaboration between the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and WHO as part of WHO’s initiative to eliminate congenital syphilis. This study implemented a new rapid diagnostic test to increase access to prenatal syphilis testing in low resource settings with the aim to show the feasibility, cost effectiveness, and impact of a rapid diagnostic to contribute to elimination of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of syphilis.

The ultimate goal of this work was not just the successful completion of a study to show effectiveness, but to use this evidence to drive policy change. We worked across many diverse countries including China, Peru, Brazil, Uganda, and Zambia. All countries were able to change national policy to incorporate widespread use of rapid diagnostic tests for detecting syphilis in pregnancy. In Zambia, we were able to drive policy change, but also work with the Ministry of Health to include procurement of this diagnostic into the national budget and supply chain. Often in public health, we don’t see the immediate impact of our work, but this time it was very clear and very rewarding.

AL: I am proudest of analysis of Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (PHIA) data to provide evidence of the potential impact of climate change on HIV transmission. In this PHIA study we showed that climate change can have a variety of human-centered impacts, particularly on women. For example, some women who can no longer support themselves through subsistence farming – due to variable weather and other climatic impacts – are turning to sex work, which becomes a vector of HIV transmission. We found that food aid to women can be a factor that decreases this risk, but other types of economic aid may not. With this information, we can begin to consider steps forward in addressing these connected issues and potentially consider modeling food insecurity, climate change, and the HIV epidemic together.

AH: Establishing the Global HIV Implementation Science Research Training Fellowship at ICAP has given me the opportunity to train and mentor a group of very talented pre- and postdoctoral fellows in interdisciplinary approaches to rigorously test interventions to improve the uptake, implementation, and translation of scientific findings into standard of care, as well as to evaluate the impact of bringing such interventions to scale.

Q: Describe your journey to science – who inspired you and what type of legacy do you want to leave for women who come after you?

JF: Wafaa El-Sadr and Sharon Mannheimer inspired me from the beginning and continue to do so. Yes, with the sheer force of their intellect, but much more so by the profound humanity they manifest in every part of their work. As I entered the field 20 years ago, I interacted with their patients at Harlem Hospital, and I came to see them both through their patients’ eyes as unwavering allies in hundreds of individuals’ journeys towards health and healing.

SMS: Lillian Wald, a public health nurse who worked in the tenements of NYC at the turn of the 20th century, inspired me. She founded many public health and welfare organizations that are still in existence today, including the Visiting Nurse Service. I don’t care about my legacy; I just want people to be healthy and thrive.

AL: My journey to research was long, expensive, and circuitous, as it came from a medical career. It has often been hard to find mentors, something that is more common among women than men. However, I have met amazing women in public health research, and have been particularly inspired by historical women such as Barbara McClintock and Rosalind Franklin, who achieved so much under difficult circumstances. I hope that I serve as a good mentor, and that women in the future get the same opportunities as men, without people using preconceptions about women’s natural talents to diminish their achievements.

AH: I became interested in medicine and science at a very young age. My dolls were my patients, and as a child I owned a microscope and a chemistry set. I never considered a career other than one in the sciences. I was fortunate to have parents and teachers who encouraged me to pursue my passion. It is my hope that the next generation of girls and women interested in science are supported to realize their aspirations as well.

Q. What kind of support do you think could help women to overcome obstacles and achieve their full potential in the field of science?

JF: I remember ICAP Haiti country director Barbara Roussel saying, “Don’t let others’ opinions influence your path, and don’t worry about speaking last. Being the last to talk gives you more time to listen, to analyze, and to identify the gaps that can inspire you to come up with solutions.” The inspiring women at the head of ICAP country teams and the leadership in NYC are also examples of how far you can go if you push against gender-based barriers, including for some of us, the barriers in your head. None of them were born into leadership; they grew to meet historic challenges and it made them the powerful leaders they are.

——————————

About ICAP

A major global health organization that has been improving public health in countries around the world for nearly two decades, ICAP works to transform the health of populations through innovation, science, and global collaboration. Based at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, ICAP has projects in more than 30 countries, working side-by-side with ministries of health and local governmental, non-governmental, academic, and community partners to confront some of the world’s greatest health challenges. Through evidence-informed programs, meaningful research, tailored technical assistance, effective training and education programs, and rigorous surveillance to measure and evaluate the impact of public health interventions, ICAP aims to realize a global vision of healthy people, empowered communities, and thriving societies. Online at icap.columbia.edu