With the global surge in coronavirus cases causing an ongoing global health emergency, ICAP has been playing a lead role in the global response to the pandemic. In contrast to many of the organizations taking action against COVID-19, however, women are leading much of ICAP’s planning and execution of this lifesaving work. From our field offices in sub-Saharan Africa to our headquarters in New York City, ICAP’s women leaders are spearheading care, treatment, research, and training programs in response to what may be the greatest health crisis of our time.

As part of our continuing series on the dynamic women at the forefront of ICAP’s global health efforts, we spoke with three leaders at the forefront of ICAP’s work and asked them to reflect on what it means to be a woman professional in global public health.

Florence Bayoa, MA, is the country director for ICAP in South Sudan. She is an accomplished international development professional with over 20 years of experience working on health, nutrition, HIV, gender, and youth empowerment projects in the government and civil society sectors.

Fatima Tsiouris, MS, is the deputy director for human resources for health (HRH) development at ICAP at Columbia University. She also leads ICAP’s work on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), HIV nutrition, and global health student training programs.

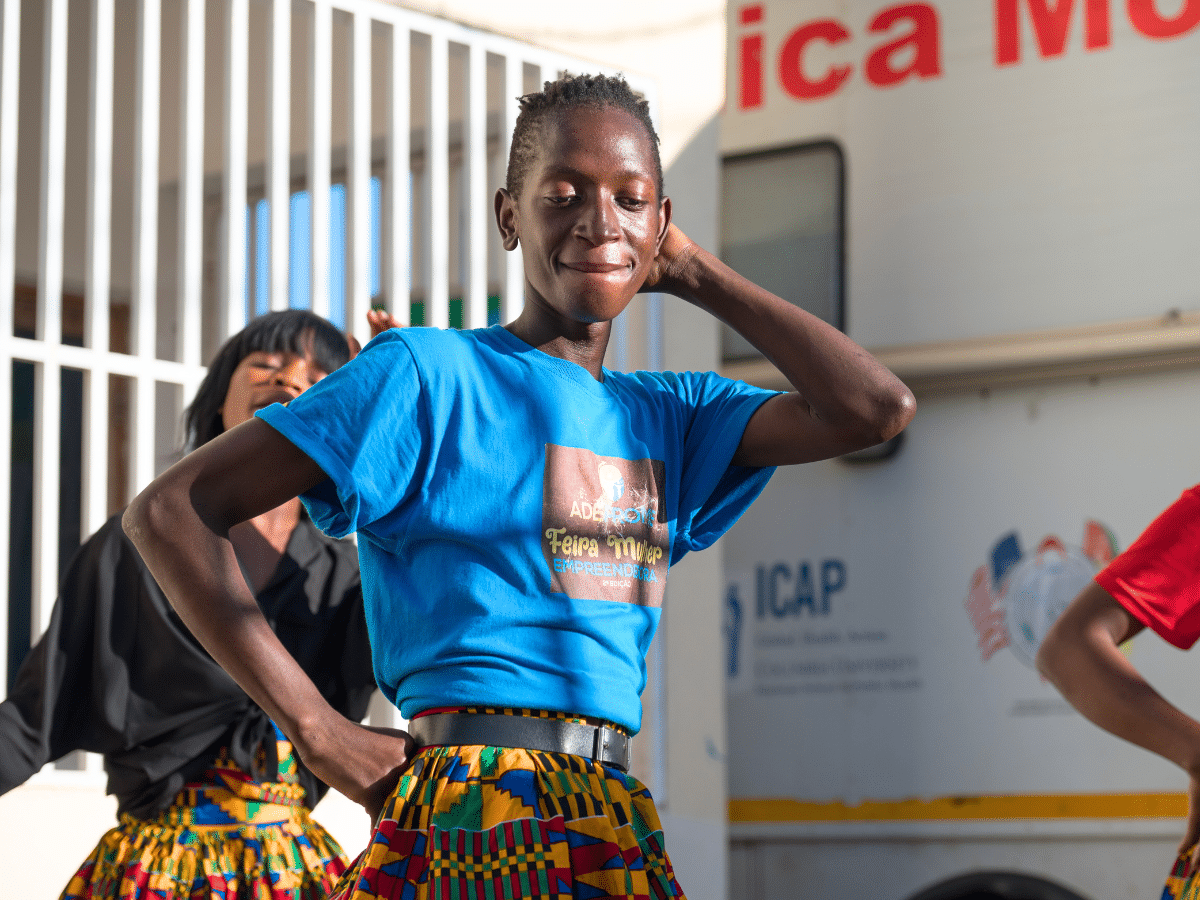

And Mirriah Vitale, MPH, is the country director for ICAP in Mozambique. She has over 15 years’ experience in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of HIV/AIDS programs globally.

In this Q&A, they share their triumphs, advice, and aspirations.

Q: Being a woman is often framed as being a disadvantage, but are there times or circumstances where it has been an advantage, especially within the public health sector?

MV: I would argue that being a woman is always an advantage. Particularly mothers—we have an innate ability to multitask, think outside the box, and work under pressure, given the layers of responsibilities in our lives. This is a particular strength in the public health sector, where change is constant, and challenges are many. Public health requires strategic thinkers who can act and respond quickly and dynamically, considering not only what is best for the world, but also what is best for our families and communities.

FT: Absolutely! Early in my career, I worked with colleagues to develop breastfeeding materials for women living with HIV. Still, it wasn’t until I went through motherhood and breastfeeding myself that I truly understood the challenges of developing guidelines and tools while being removed from the situation or condition. I remember coming back from maternity leave and saying: “we need to revisit these materials—they don’t speak to the realities and the challenges of breastfeeding that we need to address.” I think this was quite formative in developing my strengths in taking policy and recommendations and thinking through how to implement them.

FB: Framing womanhood as a disadvantage is derived from gender bias. Personally, it has been an advantage, especially in the health sector. I have worked for several years as a nutritionist managing children under five years, and in HIV prevention, care, and treatment. African communities see women as compassionate, trustworthy, caring counselors, and as such, the advice a woman provides is valued when it comes to health. In most communities, women play significant roles. They are the caretakers of the entire household when it comes to health conditions, and women prefer talking to fellow women to counsel them on health issues. These circumstances have made my career easy and I have seen clients adhering to treatment and lives saved.

Q: How have your experiences as leader in public health shaped your response to what is now a major global health crisis?

FT: My experiences have shaped my response to this pandemic by teaching me the importance of following the science, and the importance of good quality data in designing and implementing public health approaches and interventions. Education and the way we approach knowledge transfer is fundamental to public health. Being able to translate complicated guidelines into simplified implementation approaches that take into account the population as well as the resources available is so important. This learning has also been applied to our response to COVID, especially in the context of training front-line health workers in resource-limited settings on how to protect themselves and their patients—focusing on what we do know to formulate how we respond.

FB: Women have always been disadvantaged and affected differently in times of crises. With the appearance of COVID-19, the gender differences have gone even deeper. Women are the majority workers in all health and social services—that exposes them to more risk. The majority of women are casual workers, and many have lost their jobs. Women are known to shoulder unpaid responsibilities at family and community levels. With the pandemic, this trend is expected to be aggravated. In South Sudan, it has been reported that sexual and gender-based violence increased during the COVID-19 lock down. Therefore, it is a matter of urgency to support and empower women with knowledge and resources. The unique situation of women needs to be taken into consideration while responding to social, economic crisis, and health security issues.

MV: This year, 2020, has been a challenging one. The global COVID-19 pandemic has pushed us in so many ways, as public health professionals, leaders, parents, individuals. We’ve lost colleagues and friends and have been forced to readjust our work, our homes, and our personal lives to a new reality—one that is often overwhelming and relentless. In Mozambique, ICAP has played a pivotal role in implementing a coordinated response to COVID-19 in Nampula province, one of the provinces most affected to date. We are working tirelessly to support the government, provincial leaders, and healthcare workers to implement targeted strategies to prevent and mitigate the impact of the pandemic, while ensuring continuity of HIV prevention, care, and treatment services and reducing stigma and discrimination related to both HIV and COVID-19. This has required a delicate balancing act to ensure we are responsive, innovative, and forward thinking, while considering the personal impact this global health crisis has on each one of us. Every day I’m impressed by the resilience and unwavering dedication I see in so many of my colleagues. The collective perseverance and willingness to go above and beyond. As we adjust our programs and strategies to align with the new normal, I’m hopeful that the lessons we’re learning will help pave the way for future programs

Q: What is the best advice you’ve received as a career woman? What advice would you give to young women looking to work in the health care sector?

FT: Challenge yourself—and allow yourself to be challenged by situations, people, work—most often, these are opportunities for learning and growth.

MV: The best advice I received was to not be afraid of the big or little things that often stand in our path. Forge on, and a solution will be found! This advice didn’t come from one specific person; rather, it came from all the women who blazed the trail ahead of me, demonstrating their strength, leadership, and incredible impact around the world. For young people looking to make a career in public health, I would let them know that public health ticks the box of never a dull moment. It’s exhausting and exciting at the same time, constantly changing and always pushing us to think and dream bigger, try harder, and build stronger, more resilient projects, programs, people! It’s hard work—but you will love it.

FB: The best advice I received was from my late father, he told me: “you are my firstborn, and I give you all the rights I would have given my first son. Keep in mind that you can do what a man can do,” he said. I grew up knowing I can do what men can do and even better. I advise young women to take up a career in health and shunt away from the discouraging slogan that sciences and engineering are for men. Women are the best health workers in the world. Grow tough skin and let your work speak.

Q: What are your aspirations for the women of the next generation? What do you hope for them, and what do you want to see the women of the next generation achieve?

FB: My aspiration for the women of the next generation is to challenge stereotypes and take up science and engineering roles. In the next generation, I would want to see more women leaders in science, technology, and innovation.

MV: Peace on Earth! And an actual work/life balance. 😊

FT: I want to see women in more leadership positions—that’s a given. I also want to see a society that is progressive and supportive of women who desire to have families and continue to work—that the hurdles that exist currently, which may preclude women from doing both, are a thing of the past. We need women leaders to push this.

The ICAP Women Leaders Around the World Q&A series highlights the triumphs and challenges of women at the forefront of shaping policy and decision-making in global public health.

A global health leader since 2003, ICAP was founded at Columbia University with one overarching goal: to improve the health of families and communities. Together with its partners—ministries of health, large multilaterals, health care providers, and patients—ICAP strives for a world where health is available to all. To date, ICAP has addressed major public health challenges and the needs of local health systems through 6,000 sites across more than 30 countries.