In the Kyrgyz Republic, injection drug use accounts for almost 60 percent of HIVinfections. For people who inject drugs, needle and syringe programs—which provide clean needles and syringes at no cost to participants—serve as one of three core HIVinterventions, along with opioid substitution therapy and HIV testing and counseling.

A recently published study conducted by ICAP, in close partnership with the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan, local NGOs, and the Centers for Disease Control in Central Asia, reveals stark realities faced by people who inject drugs when accessing these services, but also upholds their enduring value.

The study, funded by the US Key Population Implementation Science (KPIS) fund, is one of the first assessments in the Kyrgyz Republic examining barriers and facilitators that affect participation in needle and syringe programs by people who inject drugs.

The 2015 assessment, conducted at 19 needle and syringe program sites in six cities in Kyrgyzstan, involved interviews with 24 needle exchange program staff and 10 focus groups with nearly 100 male and female participants. Researchers collected information on program processes, quality, and availability of other on-site services such as HIV rapid testing and social support, along with existing challenges in delivering services.

“Making these services more accessible and attractive to people who inject drugs can aid national HIV prevention efforts,” said Dr. Anna Deryabina, regional director for ICAP in Central Asia and the lead author of the study. “Efforts to track participation and information on the quality of program services are sparse, so it was important we try to fill those gaps.”

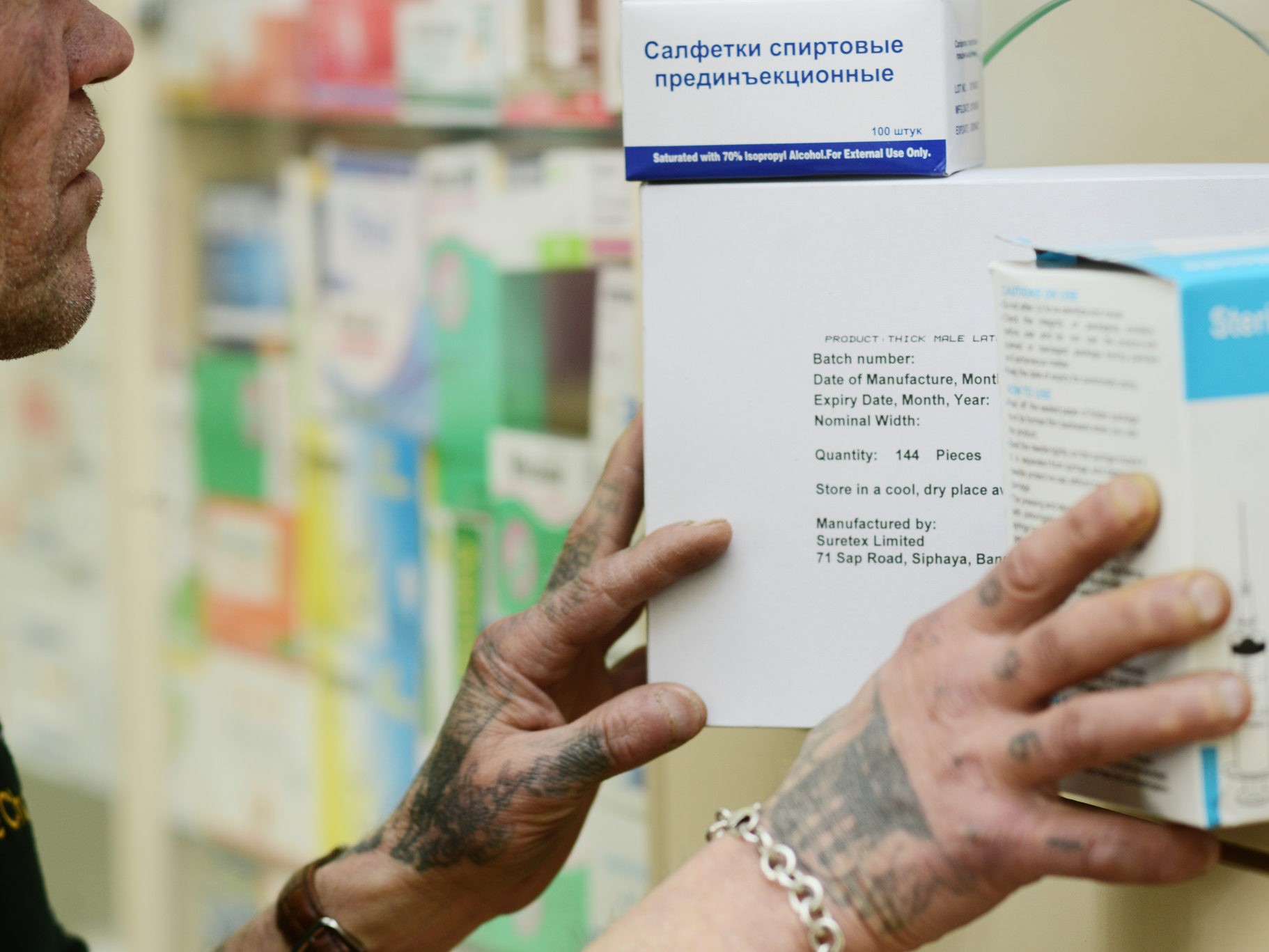

With HIV prevalence in this population varying from six to 17 percent depending on the region, and an estimated 25,500 people who inject drugs living in the country in 2013, the availability of needle and syringe programs has been shown to have a significant impact in reducing unsafe injecting practices in the Kyrgyz Republic. Many programs also provide condoms, naloxone kits to treat opiate overdose, education, and outreach services. Although they remain the first, and at times only, point of contact for health care services for people who inject drugs, several barriers can deter clients from accessing these lifesaving programs.

In Kyrgyzstan, all persons diagnosed with drug dependence are required to register for government treatment services. Although this is meant to help in planning services, program staff say that registering with narcology services often means a person is added to the police register, which can lead to losing their driver’s license and being under continuous police surveillance. Even though needle and syringe programs do not require clients to be registered, there is still a fear that being seen at the program site or using services may lead to trouble with the police, job loss, or social stigma if friends or family find out.

“We always tell them that all services are confidential, but they are afraid that the information about them will be shared with the police.”

—Program staff member, Osh

Overall, the study found that access to needle and syringe programs was mainly limited by such factors as: stigma and discrimination around drug use; fear of police encounters, including when conducting required return of used equipment; lack of trust in both program staff and other drug users; limited geographic presence of program sites and inconvenient hours of operation; and lack of information and motivation to utilize services.

At the same time, availability of outreach services and additional health services were highly valued, and seen as an important way to stop the spread of disease like HIV.

The study participants offered insights into ways to increase participation by persons who inject drugs, including: discreet locations to ensure anonymity; free distribution of supplies and referrals to other services; deployment of more direct outreach workers to provide community-based services; and accessible information, especially for those who are younger, less experienced, or isolated.

“Now there are no problems with syringes, but we need more information. It is important to inform youth about consequences. And [also important for] people to have a chance to talk to each other.”

− Male participant, Osh

To ensure that key stakeholders were engaged in discussion of the study results, preliminary findings were shared with a wide range of national and international partners working with people who inject drugs in the Kyrgyz Republic.

“First and foremost, we need to make sure people know that needle and syringe exchange program services are available. It’s also very important that these programs are shaped by the recipients of the services,” said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, ICAP’s global director and a co-author of the study. “We know that these services work. It is up to us to break down the barriers so we can get closer to stopping the spread of HIV in Central Asia.”

Learn more about ICAP’s work in Central Asia in Where We Work