A decade ago, today’s progress towards confronting the global HIV epidemic would have been unimaginable. The commitment of affected countries and communities combined with a remarkable global response has enabled nearly 21 million people – half of those living with HIV – to access life-saving HIV treatment. Treatment has transformed HIV into a chronic, but manageable, illness.

Although much has been accomplished by using the public health approach to find people living with HIV, engage them in care, and provide treatment and important supportive services, much more needs to be done.

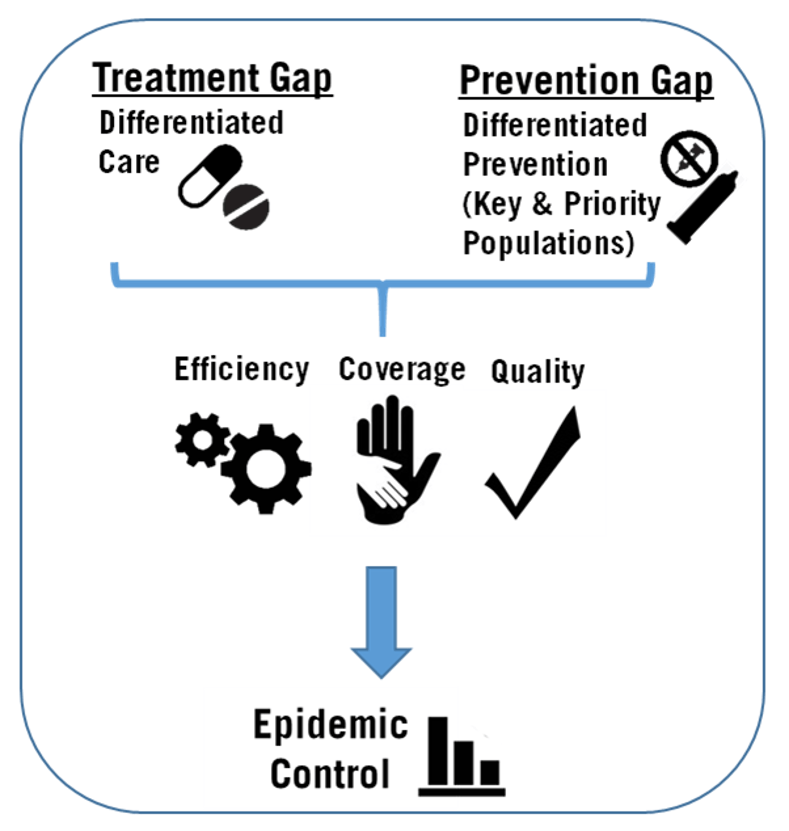

In a recent commentary published in PLOS Medicine, Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, ICAP’s global director, and colleagues discuss tailored approaches to treatment and prevention of HIVinfection, and an important new strategy called differentiated service delivery, or “DSD”.

Using the streamlined and consistent public health approach enabled a remarkable scale-up of treatment. Standardized strategies for patient management, drug purchasing and distribution, laboratory testing, and documentation facilitated the rapid expansion of HIVprograms, even in settings with limited numbers of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and laboratory experts.

Critically, this systematic approach enabled simple and clear messages for both patients and health workers, and allowed HIV treatment to be provided by the breadth of health care providers, including physicians, nurses, medical officers, and community health workers.

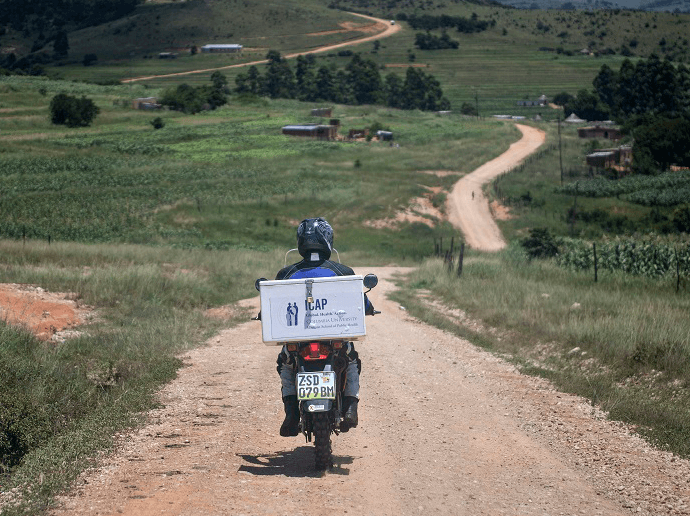

In order to reach global goals, however, another 10 million people living with HIV need to start treatment in the next three years. This won’t be easy, especially as resources have plateaued due to the misperception that the AIDS crisis is over. In many of the places most severely affected by HIV, fragile health systems translate to overwhelmed health workers and crowded clinics. Patients have to travel long distances to reach health facilities, taking them away from their families and jobs and creating financial burdens.

“Extending HIV prevention and treatment services to those not yet reached is a global priority,” said Dr. Miriam Rabkin, ICAP’s director for health systems strategies and one of the authors of the article. “When we look ahead to the reaching the ultimate goal—epidemic control— it’s clear that what got us here—the public health approach—won’t get us there. We need to retain the key elements that made this strategy so effective, while continuing to innovate.”

DSD focuses on tailoring services for different groups of patients based on their unique needs. While most of the attention to date has focused on the “what” of HIV treatment—what counseling to provide, what drugs to use—DSD addresses the “how.” This may mean adjusting service intensity, location, and frequency, as well as the type of health worker to fit the needs of specific groups of patients.

One DSD model involves community based treatment groups. First developed in Mozambique, the approach enables people living with HIV to provide support for each other in the community, while one member of the group returns to the clinic each month to get checked, report on the other members, and pick up medications for all. It’s a patient-centered approach that leverages the ability of individuals with HIV to self-manage their health, support and collaborate with each other, and avoid long waits at congested clinics.

DSD models can also be implemented in health facilities. Appointment spacing, for example, provides stable patients the option to shift from quarterly to twice-yearly appointments, creating efficiencies both for patients and for the health system. ICAP in Ethiopia, under the leadership of the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), is currently conducting an appointment spacing pilot project at six high-volume hospitals. Based on early promising results from the CDC-funded pilot, appointment spacing is now being scaled up to hundreds of health care facilities nationwide.

DSD models are also needed for groups of persons living with HIV with unique needs like pregnant women, adolescents, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who inject drugs. The latter groups bear a disproportionate burden of HIV and face major societal barriers, such as stigma and discrimination, that stand in the way of access to vital services. Engaging members of these communities in designing, testing, and implementing DSD models is fundamental to their success.

“Patients and communities have always been central to the AIDS response,” said Dr. El-Sadr. “As the public health approach evolves into DSD strategies, let us seize the opportunity to learn from their commitment and innovations.”