In 2014, West Africa faced the largest health emergency in its history with the rapid community spread of Ebola, a virus that is highly transmissible and causes a life-threatening hemorrhagic fever. As we face the worldwide outbreak of a novel coronavirus disease for which there is no known cure or vaccine, we have much to learn from how the global health community united to implement stringent infection prevention and control procedures in communities and health facilities to halt transmission of Ebola.

The Ebola epidemic that raged in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia between 2014–2016 was the largest in history, killing thousands of people, ravaging health systems, and crippling economies. Communities lived in intense fear of infection and painful deaths.

Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia are among the poorest countries in the world, and at the time of the Ebola outbreak, their health systems had been further weakened by civil war. They confronted the epidemic with scarce resources, limited infrastructure, and an appalling shortage of health care workers. Even prior to the Ebola outbreak, these countries had only one or two doctors for every 100,000 people, and health care workers were especially prone to contracting the deadly disease, given their exposure to infectious patients. Ebola took the lives of numerous doctors and nurses, wiping out critical knowledge and skills and depriving front line health workers of inspiring role models in dark times.

While many factors contributed to the community spread of Ebola, a lack of adequate infection prevention and control practices, or IPC, led to the high proportion of infected medical staff. These included the absence of appropriate triage procedures; insufficient access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and other needed supplies; and inadequate infection controls, including basic hygiene practices—all of which we see in today’s response to the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. As deaths in the community from Ebola mounted, heroic health workers developed and implemented workplace protections and protocols that successfully halted the spread of the virus a year after the epidemic started. Scores of nurses and health care workers died in the interim. Implementing lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak will prove to be critical in our response to the current coronavirus pandemic.

ICAP’s Emergency Response in Sierra Leone

Over a six-year period starting in 2012, Sierra Leone faced a series of devastating natural disasters and public health emergencies including massive floods, mudslides, cholera outbreaks, and the spread of Ebola. The complex environment created by these simultaneous public emergencies strained the country’s public health system, with many health care providers giving their lives in order to treat their patients throughout the ongoing state of emergency. The public health response was further stymied by limited access to treatment centers, which forced people with suspected Ebola virus disease to remain in the community and for families to care for such individuals at home, putting caregivers and household members at high risk of infection.

Rapid Assessments of Community Care Centers

At the height of the epidemic, ICAP provided rapid assessments of community care centers, at the time a new model of care for the government of Sierra Leone, across six severely impacted districts. This data, combined with 58 interviews with national and regional stakeholders, helped key decision makers to better understand how the newly implemented model of care was being implemented across the country and where improvements could be made to improve patient health outcomes. The results of this assessment were published in The Lancet.

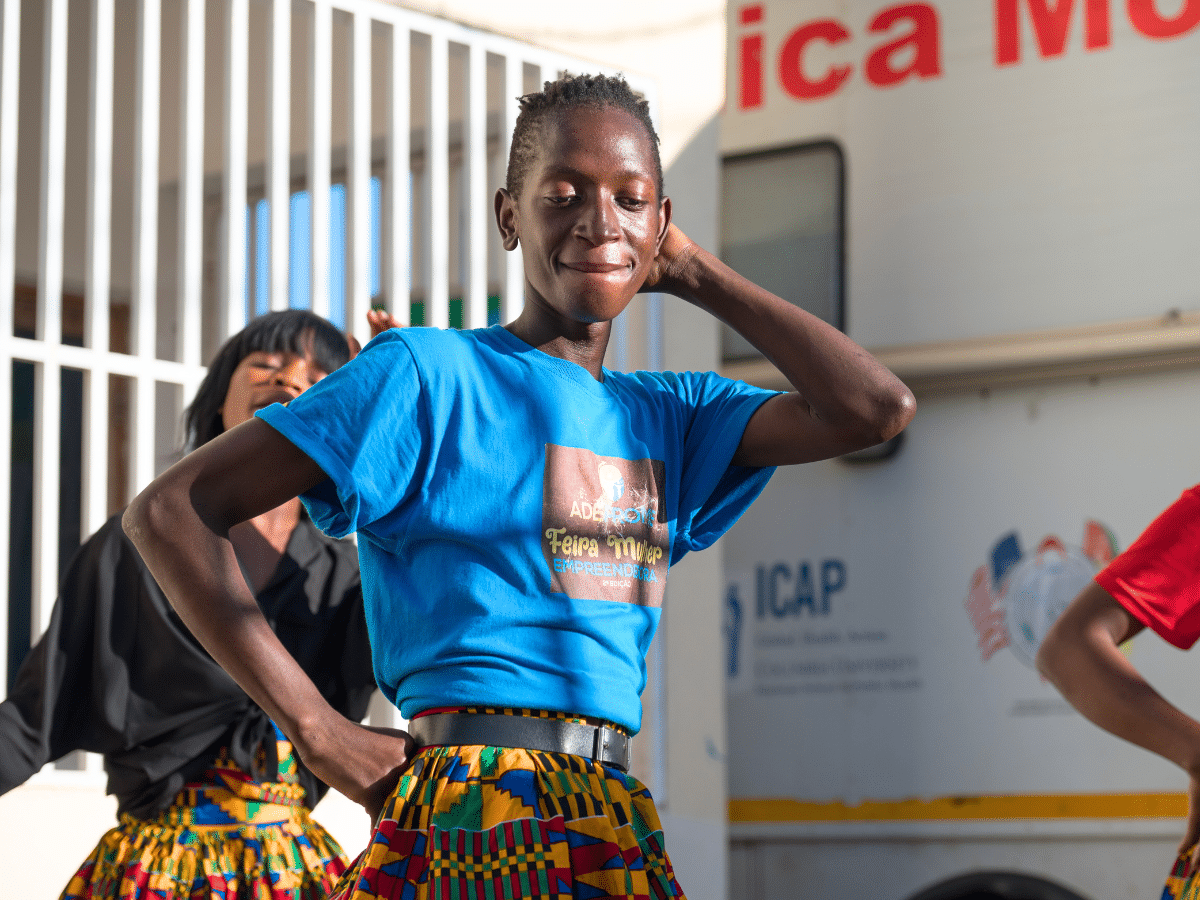

Facing the gravity of the outbreak and the scarce resources at hand, the Government of Sierra Leone developed innovative but untested approaches to confront the Ebola threat, like the facility pictured here. ICAP’s assessment at the height of the epidemic provided critical insight into their effectiveness as a health care model.

ICAP’s Post-Emergency Response in Sierra Leone

The Ebola outbreak was a particularly challenging time for the country, and especially so for its health care providers. It is estimated that as many as one in five (or 21%) of Sierra Leone’s health workers died from the highly contagious virus. Health care providers on the front lines of the outbreak faced shortages of equipment and training on IPC.

Under the leadership of the Sierra Leonean government, efforts made in the post-emergency response have emphasized the importance of IPC knowledge and skills among health workers as the cornerstone of a strong and resilient public health system. Building on its close partnership with Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS), ICAP expanded its technical assistance to include a robust series of interventions to build local expertise in IPC and to strengthen capacities of health systems in the country.

These interventions, funded by multiple partners, leverage ICAP’s decades of experience and technical expertise in infectious disease prevention, care, and treatment work to strengthen the country’s ability to respond to the next outbreak of disease or any public emergency.

ICAP aims to build a cadre of IPC specialists and IPC-competent frontline health workers across the country, building health system resiliency and responsiveness through quality improvement and human resource development.

Improving the Quality of Health Services

In the wake of the epidemic, ICAP partnered with Sierra Leone’s MoHS on a number of interventions designed to build a more resilient health system better equipped to respond to future health emergencies. Interventions included providing technical assistance on monitoring and evaluation to the National Infection Prevention and Control Unit at the Ministry; supporting the development of quality assurance and quality improvement (QA/QI) capacity; conducting infection prevention and control and malaria program evaluations; and partnering with the MOHS Nursing Directorate to support the development of pre-service nursing curricula and continuing professional development. The initiative was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Findings from the project were published in the International Journal for Quality in Health Care.

Training Health Workers in Infection Prevention and Control

In addition to its systems-level work, ICAP is also training nurses and midwives in IPC through two continuing professional development (CPD) courses. Supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Health Resources Service Administration (HRSA), the two courses include an advanced certification for specialists as well as a basic course for all nurses. Both courses include real-world simulation exercises to ensure health workers are equipped to use the skills and competencies they have developed in their daily work lives.

With support from CDC and HRSA, ICAP aims to build a cadre of IPC specialists and IPC-competent frontline health workers across the country, strengthening health system resiliency and responsiveness through quality improvement and human resource development. ICAP led the design and development of a six-month IPC certificate course, which combines classroom training with simulations and hands-on assignments to train a new cadre of IPC specialists. After completing the course, graduates return to their workplaces, where the training’s impact ripples outwards. IPC-certified health workers then serve as leaders of all aspects of infection prevention and control at the hospitals and health centers where they work.

“Having an advanced IPC certification course for us is very important because we want to have a pool of expertise in IPC who can be mentored on how to coach the remaining healthcare workers to improve the face of the health service delivery,” said Christian Kallon, acting IPC National Coordinator at the Ministry of Health and Sanitation.

The ongoing training for health care workers has increased knowledge of IPC practices and helped ensure a safe working environment for everyone, with lower risk of health care-associated infections.

With the graduation of the first cadre of ICAP-trained IPC specialists in early 2020, Sierra Leone now has champions of IPC methods placed throughout the health system. Through the HRSA-funded courses, nurses and midwives can continually refresh their knowledge in the key components of IPC needed to protect themselves, their patients, and their communities. These results speak to the advantages of introducing IPC trainings to service providers at all levels of the health system. Future trainings and evaluation results will inform updates of materials and build the case for course accreditation and the inclusion of the ICAP-developed trainings in national IPC strategies.

Modeling Best Practices in Real-World Contexts for the Midwives of Tomorrow

The ICAP-led establishment of Sierra Leone’s first-ever model ward for nursing and midwifery gives health service providers with a real-world example of the integration of IPC practices in a clinic setting. Thanks to an innovative collaboration between the Princess Christian Maternity Hospital and the National School of Midwifery, the facility offers regular in-service trainings for hospital staff, trainees, and students.

The ongoing training for health care workers has increased knowledge of IPC practices and helped ensure a safer environment for staff and patients alike, reducing the risk of health care-associated infections. Additionally, the project has supported community sensitization and hand hygiene campaigns, which have resulted in increased awareness of IPC at the community level. This model ward serves as an example of how to sustain IPC measures in low resource settings.

ICAP’s work in Sierra Leone will help nurses in communities play an active role in ensuring strong outreach from clinic to community.

Looking forward

While the current COVID-19 outbreak is evolving at a dizzying pace, experience from China, Hong Kong, and elsewhere has shown that testing, tracking, isolation, and quarantine combined with meticulous IPC can mitigate the worst impacts of the novel coronavirus. Despite its proximity to the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, Hong Kong swiftly ramped up screening criteria and worked to quickly isolate infected patients in airborne infection isolation facilities. At the time of writing, no Hong Kong health workers had been reported infected.

ICAP’s Susan Michaels-Strasser, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN, senior director for human resources for health development, has emphasized the role of IPC on the frontlines of COVID-19 saying: “To protect those at the frontlines in the short term, we urgently need to demand a surge in manufacturing for personal protective equipment and contingency plans for outdoor triage so that the health workers at facilities are not put at undue risk. Health facilities and systems need to define standard operating procedures, guidelines, and fail-safe systems when they are most needed.”

While nations respond to the current crisis, it is also important to look ahead to more resilient systems, much as Sierra Leone has done in the years following the Ebola outbreak. By building more resilient and well-trained frontline workers, health systems will be strengthened not only in the course of normal operation, but more importantly, in times of crisis.

This article is part of ICAP’s 2020 Year of the Nurse campaign to advocate for nurses as leaders in the international health sector and encourage discussion on how the global health world can better leverage nurses’ unique connections to the communities they serve.

With nurses at the helm advocating for patient-centered approaches in health care and health policy, practical and affordable solutions for the world’s most pressing health challenges are reachable.

Learn more about our work with, and for, nurses on our campaign page, #ThisNurseCan.

A global health leader since 2003, ICAP was founded at Columbia University with one overarching goal: to improve the health of families and communities. Together with its partners—ministries of health, large multilaterals, health care providers, and patients—ICAP strives for a world where health is available to all. To date, ICAP has addressed major public health challenges and the needs of local health systems through 6,000 sites across more than 30 countries.