Having just observed Black History Month and Women’s History Month, I am reminded that my journey to becoming an independent public health researcher is unified by one overarching commitment: improving the health of structurally marginalized populations through the lens of my own lived experience as a Black woman.

Growing up outside of two predominantly Black cities, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, I became acutely aware of the health disparities affecting people of color and as such, concerns regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion became a central focus of my professional and personal interests.

The principle and importance of public service and giving back to my community were solidified through my adolescence. My mother was the director of the D.C. Crime Victims Compensation Program, a program that provides compensation and necessary aid to victims of violent crimes. From an early age, my mom would share with me firsthand stories from the victims, who were overwhelmingly women of color and their families, and whose stories were about experiencing poverty and abuse, symptoms of more pervasive systems and structures.

Listening to the victims’ stories and volunteering with my mother in D.C. women’s shelters that served victims of domestic violence juxtaposed my own lived experience with the lives of many who looked just like me but were born into different circumstances. These early experiences did not prompt an immediate epiphany about my future career, but they did gradually provide me with insight into systemic issues of women of color at a critical time in my development as a child and adolescent.

This formative insight has undeniably guided my academic efforts toward a career in public service through public health research. During my second year in college, I pursued a degree in Community Health. Shifting my lens from an individual to the population level better aligned with how I understood the world and health distribution; . Upon completion of my undergraduate degree, I worked in Baltimore coordinating studies related to HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) within Black communities. Further motivated by my passion for research, I pursued a Master of Public Health (MPH) in Epidemiology at Tulane University in New Orleans, where I studied HIV, STI health disparities, and how interpersonal- and community-level factors influence health in Black adolescents and young adults.

However, as I continued to pursue advanced levels of higher education and to navigate academia through my undergraduate degree to my current doctoral training, I realized there are currently few women of color in academia with lived experiences and perspectives similar to my own. This highlights the inefficiency of diversity and inclusion efforts and opportunities made and provided by leading institutions.

Increasing diversity is not just a matter of equity and fairness but ultimately improves science. Academic and research institutions are gatekeepers of disciplines and, as such, their unique positions dictate the future direction of diversity as a priority. In 2020, the lynching of George Floyd led to protests that were a visceral reaction to state-sanctioned and often unpunished violence against Black people in the United States. This justified anger was further inflamed by the medical community’s status quo of not prioritizing care for people of color, despite COVID-19’s proven disproportionate impact on communities of color.

This confluence of events served as a moral awakening for many disciplines and industries, resulting in many academic and research institutions putting diversity priorities at the forefront. These institutions finally acknowledged that a lack of diversity precludes the generation of novel science, the equitable implementation of findings, and improvements to the underrepresented minority student-to-faculty pipeline. While many years of necessary progress lie ahead, efforts and improvements have been undeniable.

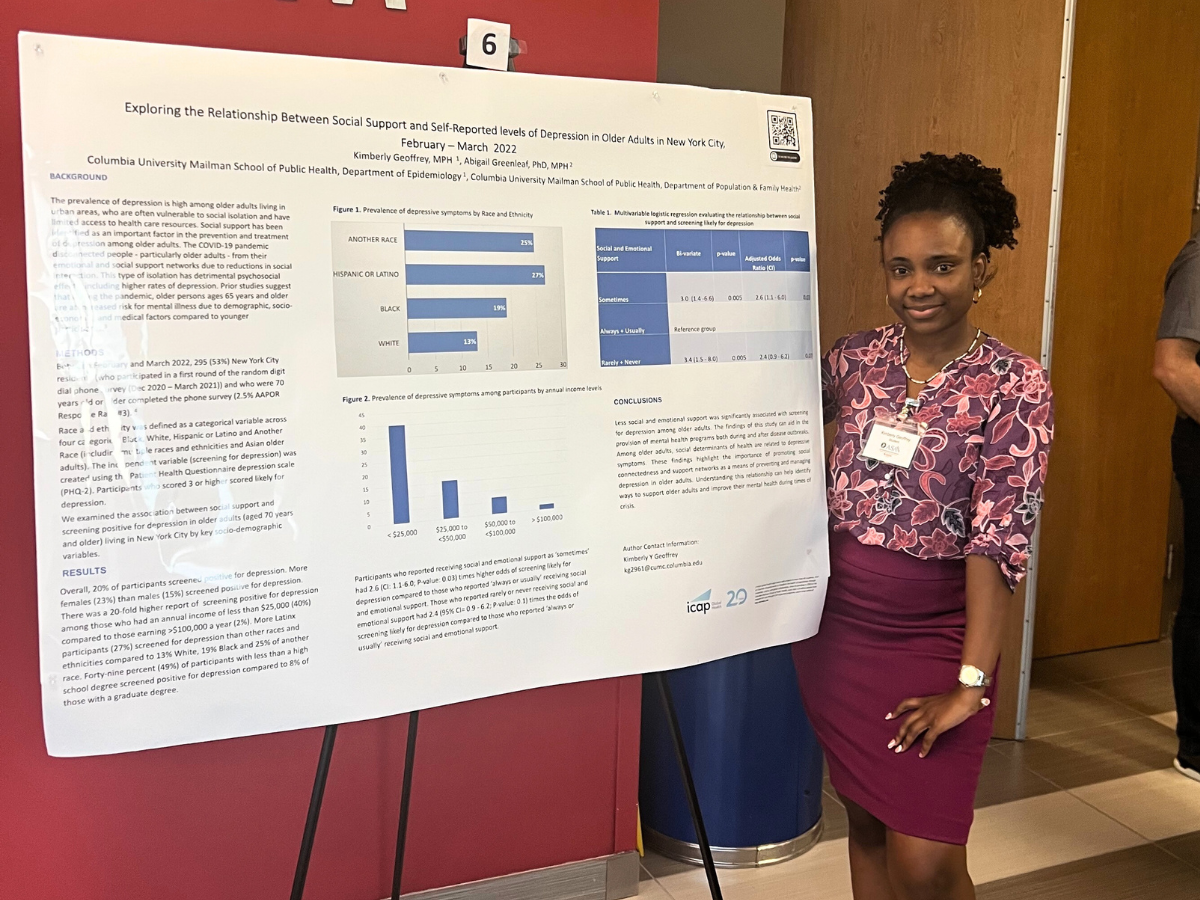

One important way to increase diversity and inclusion in academia, especially in the world of public health, is through programs like those supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the primary federal agency supporting medical research in the United States. The NIH has led multiple efforts in diversifying the scientific workforce at all stages of an individual’s career as an investigator. These initiatives suggest a sincere investment in and understanding of the importance of diversifying the scientific workforce. One such mechanism is NIH’s Mental Health Research Dissertation Grant to Enhance Workforce Diversity (R36) offered by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This grant aims to support doctoral students conducting research that align with the strategic priorities of the institute who are systematically underrepresented in biomedical, behavioral, clinical, and social sciences. I applied for this award in May 2022 through the NIMH’s Division of AIDS Research and was awarded it in February 2023; for the next 18 months, it will help fund my dissertation work.

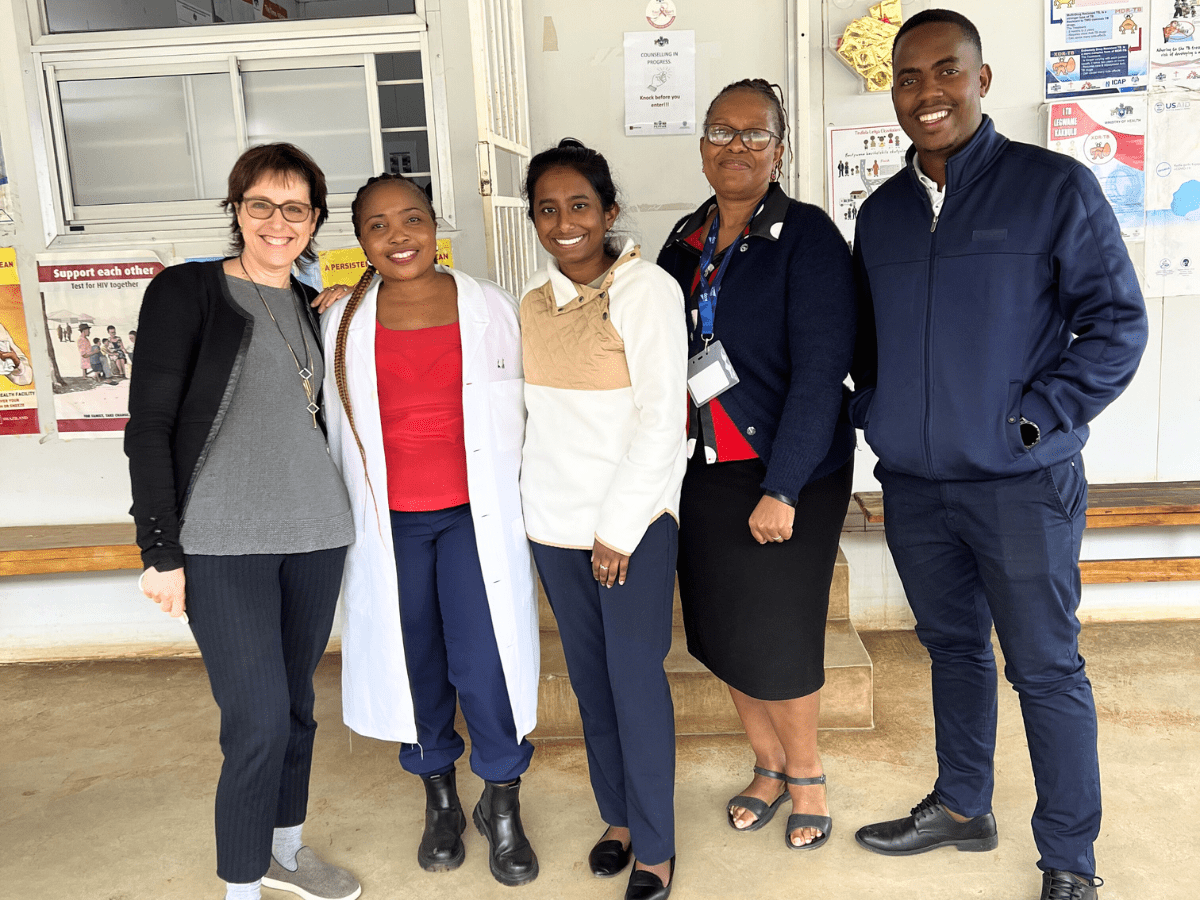

For more than three decades, adolescent girls and young women have carried the primary burden of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, the epicenter of the HIV epidemic. To date, research has prioritized understanding the individual factors that influence HIV infection, but the disparity remains. This project’s primary goal is to move beyond placing the onus of change on adolescent girls and young women and rigorously consider the societal and community factors that influence disease. This project aims to provide insight into points of intervention at the societal level that improve the equity and quality life for adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. While the specific context that reinforces and amplifies HIV risk environments may differ across the globe, women of color systematically experience pervasive inequities that limit women’s rights, whether it’s in Baltimore, New Orleans, or sub-Saharan Africa.

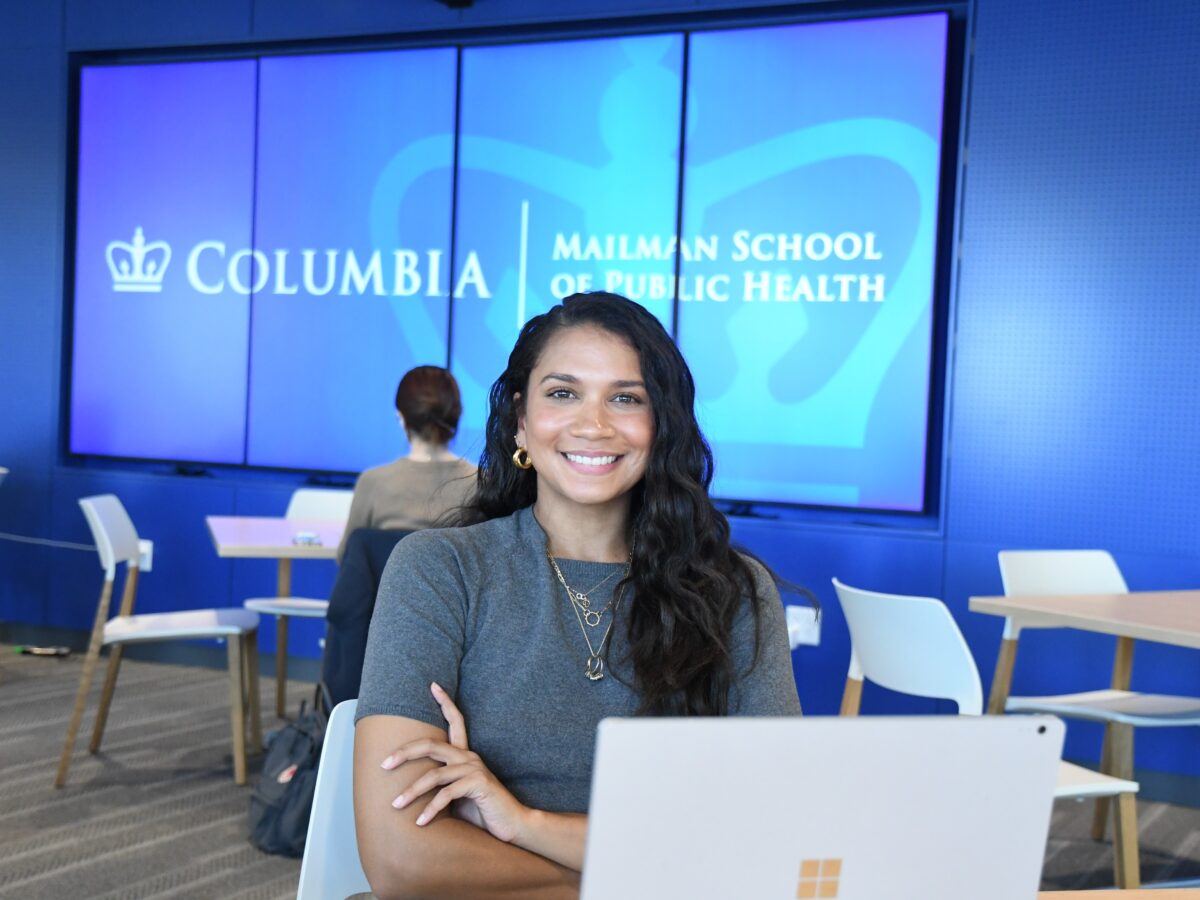

Domonique Reed, MPH

PhD Candidate, Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health

ICAP Global HIV Implementation Science Research Training Fellow