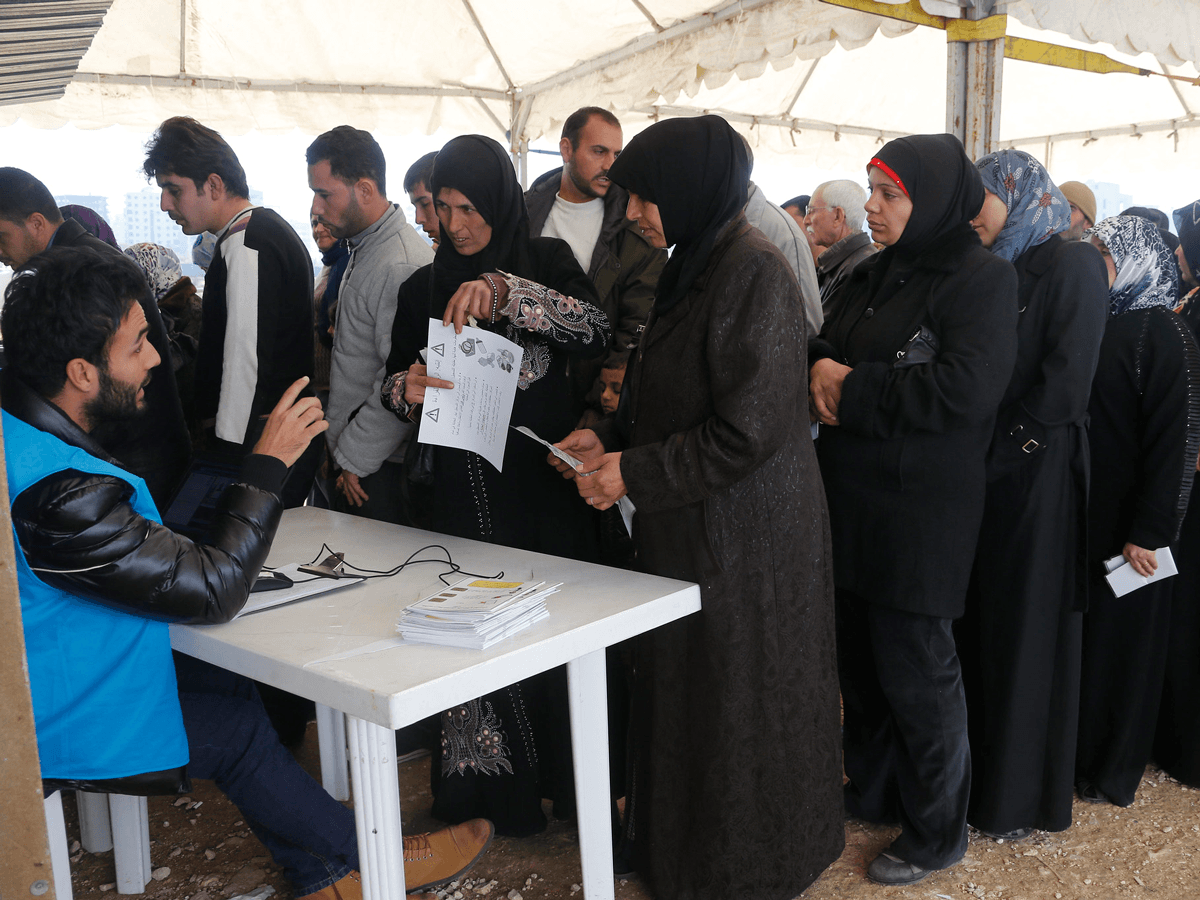

It’s a familiar scene: a family, exhausted from fleeing conflict or natural disaster waits at a crowded tent for help. Wounds get bandaged, kids get rehydrated and all receive food rations to tide them through the emergency. Everyone hopes that the crisis will pass and that this family and many others will return home.

But the reality is that most refugees do not go home. Millions remain displaced for years, if not decades.

What happens to them beyond the emergency?

How will they get the services they need to manage chronic non-communicable conditions like diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease?

These questions are at the core of ICAP’s recent work on health issues impacting Syrian refugees. Before the conflict began in 2011, Syria was a middle-income country where non-communicable diseases (NCDs) loomed large; cardiovascular disease and other NCDs were the leading causes of death. Now, Syrian refugees face both chronic NCDs as well as acute health issues associated with displacement.

A recent paper published in PLoS One, co-authored by researchers from the American University in Beirut with Wafaa El-Sadr, MD, MPH, MPA, and Miriam Rabkin, MD, MPH, from ICAP at Columbia University, explores these issues in three countries where large numbers of Syrian refugees reside: Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey.

This paper presents the first comprehensive review of literature on the burden of NCDs among displaced Syrians living in these countries, as well as the diverse health system responses.

“Although refugee health services are traditionally conceptualized as largely acute and/or episodic, the protracted nature of the crisis and the high prevalence of NCDs amongst Syrians required host country health responses to also design and deliver continuity care, including the prevention, detection and treatment of NCDs,” the authors report.

In all three countries, the response to increased demand for health services from refugee populations has been to embed refugee health care within their existing national systems. This makes sense from a health care delivery perspective, since even in Jordan and Turkey, where refugee camps exist, the majority of refugees live in host communities (79 and 83 percent, respectively, and 92 percent in Lebanon).

The authors found that the structure and financing of existing health care systems influenced their long-term ability to absorb and respond to refugee needs. In Jordan, for example, primary and secondary care were free for UNHCR-registered refugees until late 2014, after which they paid same fee as uninsured Jordanians. However, mounting costs caused the government to change their fee structure once more, and, as of February 2018, refugees now pay a much higher non-citizen rate with a 20 percent discount.

Increased out-of-pocket costs for health services, medications, and transportation are all major obstacles for refugees seeking health care, with the World Bank reporting a 60 percent decrease in health service utilization in Jordan within two years of implementing the co-payment policy in 2014. To cope with the higher cost, some individuals borrow money from family members or go into debt to pay for medical care, and some take the risky journey back to Syria in order to seek affordable, familiar care there. Others simply go without.

Since its report on decreased health service utilization in response to rising costs, the World Bank has approved two emergency projects in Jordan and Lebanon to evaluate innovative financing methods that would enable the national health systems to provide quality services both to existing vulnerable populations and to Syrian refugees. This effort would also address another important factor, which is the perceived and real impact of the increased demand from refugees on the availability of services and support for people in the host countries.

“Designing responsive health systems for refugees and displaced people has always been a challenge,” said Rabkin, ICAP’s director of health systems strategies. “One difference now is that more and more people need continuity care for chronic diseases, in addition to the acute care that most refugee health services are designed to provide. ICAP’s expertise in designing innovative chronic care delivery services in low-resource settings gives us the experience and perspective to contribute to solutions.”

With more than 15 years of experience developing and supporting programs to provide continuity care for HIV in challenging contexts—including resource-limited environments, post-conflict settings such as Cote d’Ivoire, and active conflict situations such as South Sudan—ICAP is able to apply its knowledge and expertise to the challenges of delivering NCD care to refugees and displaced populations.

“Despite the high burden of NCDs among Syrian refugees, we found limited information on delivery models, quality of care, or outcomes, signaling a need for more work in this area,” commented El-Sadr, global director of ICAP. “Novel delivery methods are needed, such as the differentiated service delivery approaches utilized in the HIV response, where systems are designed to be more accessible, affordable, and convenient in response to the needs of specific patient populations.”

ICAP’s work on refugee health was conducted in collaboration with researchers at the American University in Beirut, who have had longstanding experience and expertise in this topic and in the region. The work was supported in part by a three-year grant from the Columbia University President’s Global Innovation Fund.

To learn more about ICAP’s work on strengthening health systems to provide services to refugees and displaced populations, explore these links:

CUGH 2018 Satellite Session, March 2018: “Chronic Emergency: Strengthening Health Systems to Provide Non-Communicable Disease Services to Refugees and Displaced Populations”

Global Public Health article, May 2016: “Addressing Chronic Diseases in Protracted Emergencies: Lessons from HIV for a New Health Imperative”

Istanbul University Panel Discussion, March 2015: “Prioritizing Women: Adapting Refugee Health Services for 21st Century Health Challenges”

A global health leader since 2003, ICAP was founded at Columbia University with one overarching goal: to improve the health of families and communities. Together with its partners—ministries of health, large multilaterals, health care providers, and patients—ICAP strives for a world where health is available to all. To date, ICAP has addressed major public health challenges and the needs of local health systems through 6,000 sites across more than 30 countries. For more information about ICAP, visit: icap.columbia.edu

Photo captions—Header image: Hadji (68) gets medical support from EU funded Physical Rehabilitation Centre (EU ECHO). Photo 2: Refugees line up at the UNHCR registration center in Tripoli, Lebanon (World Bank). Photo 3: Families wait to see a nurse to vaccinate their children at the Howard Karagheusian primary health care center, in Beirut, Lebanon (World Bank). Photo 4: A refugee filling an application at the UNHCR registration center in Tripoli, Lebanon (World Bank). Photo 5: Syrian refugees, Danham Al Bilas (far right) holds and kisses his six moth old son, Mohammed in their tent in Zouq Bhanin Village, Lebanon on March 22, 2016. Denham and his family have been refugees living in this tent for the last 4 years (World Bank).