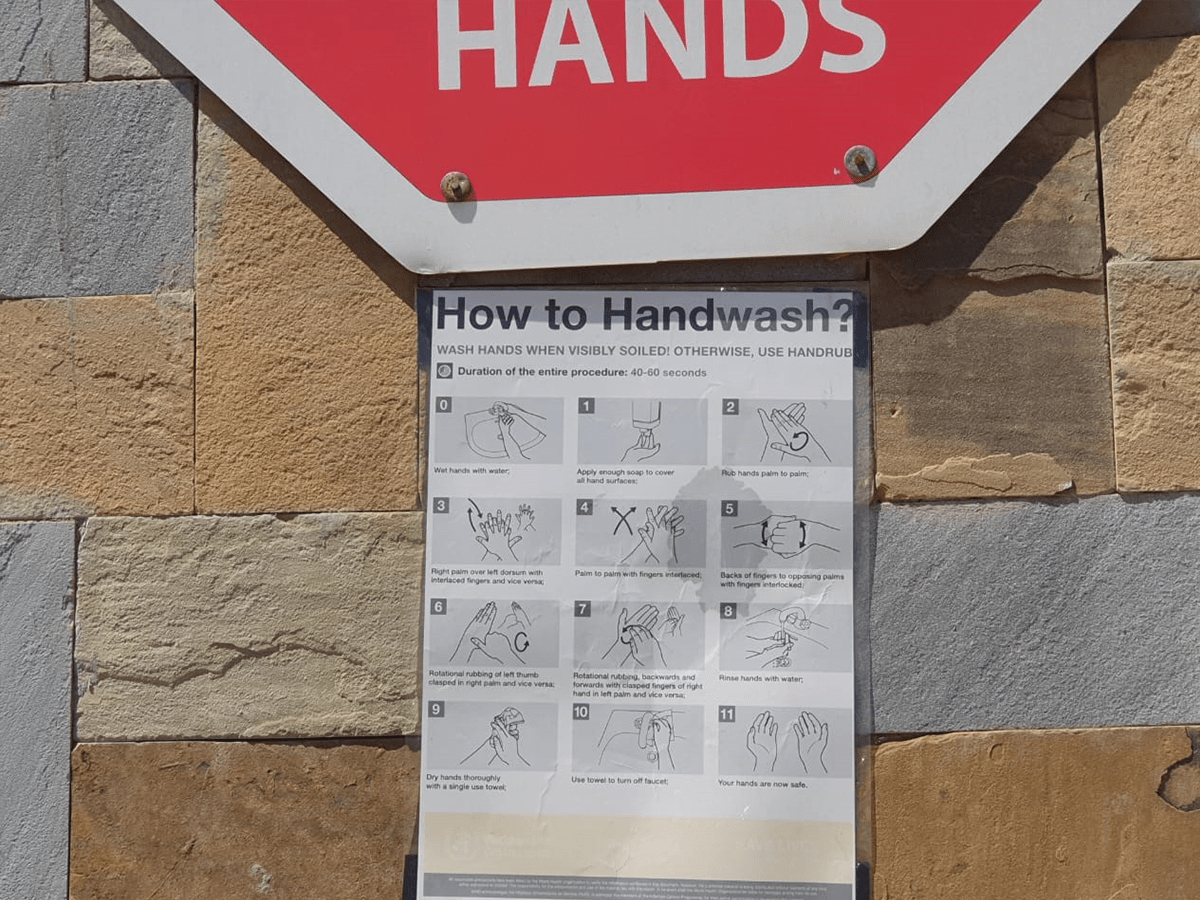

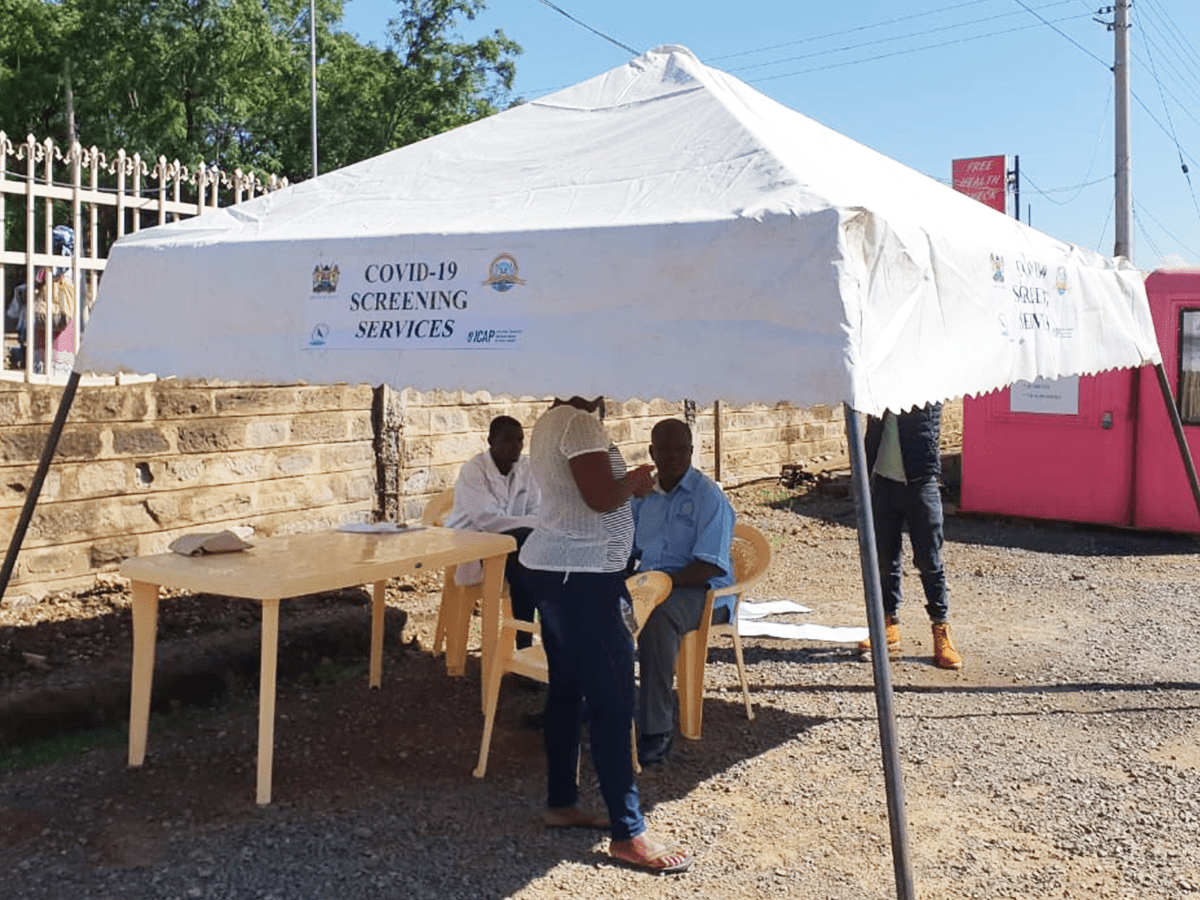

At the ICAP-supported Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) in Kisumu, Western Kenya, incoming patients, and hospital staff wash their hands with soap at a long trough sink upon entering the hospital. After washing hands, a nurse, at arm’s length, takes everyone’s temperature using a digital infrared non-contact forehead thermometer and then squirts sanitizer into people’s hands for extra protection. Then for everyone entering the hospital, it is off to one of four newly set up COVID-19 screening tent stations for extensive testing.

Two nurses at each tent screen all people for COVID-19 by recording their temperature and travel history, and taking a symptom inventory to check for a history of fever, cough, or shortness of breath to determine the extent of risk and exposure to the coronavirus.

People who have no signs or symptoms of the virus will go home. However, if someone has symptoms of the infection, a health worker provides a mask for the person to place on their face. Then the clinician in the next tent conducts a further assessment to confirm the symptoms and use an algorithm to determine if the person should go home or to the isolation ward or the intensive care unit of the hospital as defined by infection prevention control (IPC) protocols.

ICAP in Kenya developed these protocols and procedures in collaboration with JOOTRH and the County Health Department of Kisumu, with guidance from the Kenyan Ministry of Health.

“The development of standard operating procedures, protocols, and data collection indicators is to prepare for screening COVID-19,” said Doris Odera, ICAP in Kenya’s regional director for ICAP Kisumu operations. “We need to support and guide health facilities and health care providers since this is a new disease that we all have very little information about,” she said.

The standard operating procedures and protocol documents detail IPC protocols such as preventing airborne spread and contact while screening and taking care of patients with suspected coronavirus infection. Other protocols specify how to care for personal protective equipment, safely collect test samples, and take precautions to prevent airborne, contact, and droplet spread of the disease to health care workers and other people.

In addition to technical assistance, ICAP in Kenya also supported JOOTRH by providing the facility with handwashing soap and sanitizer, as well as personal protective gear such as gloves, masks, goggles, and sleeved gowns for health care workers.

As of March 25, 2020, Kisumu is yet to record a COVID-19 positive case; however, Kenya has a total of 25 confirmed coronavirus infections according to the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 dashboard, which monitors global infection rates.

“It is quite a trying time for front-line health providers, but we are taking things as they come, and trying to provide every precaution to control the spread of COVID-19,” Odera said.

A global health leader since 2003, ICAP was founded at Columbia University with one overarching goal: to improve the health of families and communities. Together with its partners—ministries of health, large multilaterals, health care providers, and patients—ICAP strives for a world where health is available to all. To date, ICAP has addressed major public health challenges and the needs of local health systems through 6,000 sites across more than 30 countries.