South Sudan, in East Africa, is the world’s youngest nation—and its birth was not an easy one. Still recuperating from four decades of conflict, earlier this year, the United Nations declared the country to be in an active famine. At the same time, like much of sub-Saharan Africa, the country suffers from a high prevalence of HIV—with an estimated 2.5 percent of the population living with HIV, and higher rates among sex workers and the military. But bringing support to the people of South Sudan is challenging to say the least: while the size of Texas, the country has only one paved road, outside its capital, Juba.

Despite the dangers and obstacles, ICAP —a global leader in HIV and health systems strengthening headquartered at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University—has worked continuously in South Sudan since 2012, drawing on its experience in crises to establish itself as the country’s largest HIV service provider.

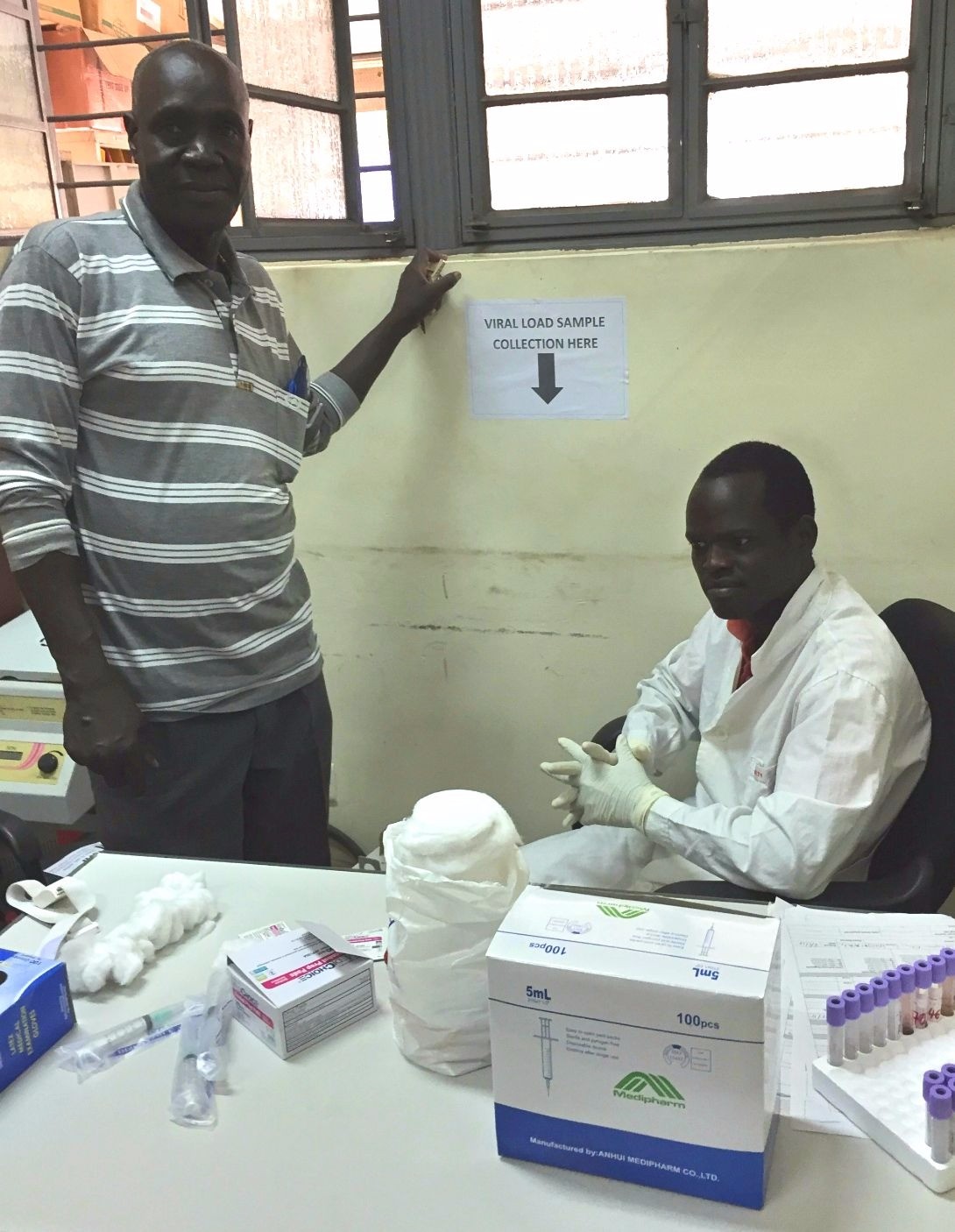

With funding through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), ICAP has successfully implemented large-scale programs to test and treat patients living with HIV in South Sudan. In the six months between October 2016 and March 2017, nearly 14,000 individuals received HIV testing and counseling and received their results at ICAP-supported facilities, and more than 1,800 started antiretroviral therapy.

Although instability continues to plague South Sudan, ICAP and its partners have persevered. When fighting broke out in Juba in 2016, leaving over 300 people dead, contingency planning helped prevent disruptions in service. At the Juba Teaching Hospital, one of the largest hospitals in South Sudan, ICAP alone provides all the support for HIV-related care and treatment. According to a nurse there, HIVpatients who were in Juba during the fighting lost everything, but were still able to come back to the facility to get antiretroviral drugs and stay on treatment.

Although instability continues to plague South Sudan, ICAP and its partners have persevered. When fighting broke out in Juba in 2016, leaving over 300 people dead, contingency planning helped prevent disruptions in service. At the Juba Teaching Hospital, one of the largest hospitals in South Sudan, ICAP alone provides all the support for HIV-related care and treatment. According to a nurse there, HIVpatients who were in Juba during the fighting lost everything, but were still able to come back to the facility to get antiretroviral drugs and stay on treatment.

Even in the face of political crisis, ICAP-supported facilities have been able to retain 70 percent of adults and children on treatment 12 months after the initiation of treatment. In addition, clinics have augmented their HIVservices for internally displaced populations. Going forward, ICAP will continue supporting health care facilities and state and national ministries of health to promote and implement a contingency planning exercise designed to sustain HIV care and treatment during periods of increased violence.

ICAP currently supports 11 health facilities in five states across South Sudan, providing direct service delivery support, training health care workers, and technical assistance. Over the last year, ICAP and partners have accelerated a number of crisis-responsive interventions to ensure safety for staff and patients and prevent service disruption. These include same-day, same-site initiation of treatment, and a reduction in the frequency of prescription renewals to reduce the number of return trips to the clinic patients need to take.

Additionally, in the coming year, ICAP will create and strengthen links between the main teaching hospital in the capital and health workers across the country— a strategy already proven successful in Namibia.

A major factor in the success of this work under such tough conditions comes from the productive partnership between CDC and ICAP. “CDC and ICAP have a strong relationship that supports our common goals, and helps achieve our mutual success here,” noted Shambel Aragaw, technical director for ICAP in South Sudan.

The CDC program in South Sudan, while one of the smallest in terms of staff, is tasked with a large job in a highly sensitive situation. Key to the success of its operation are the four South Sudanese national staff (known as foreign service nationals, or FSNs) whose long-term service forms the backbone of the program and a link between the CDC and ICAP and the government of South Sudan.

“Fighting HIV in South Sudan is very much a team effort,” Aragaw said. “Given the security challenges, ICAP has limited access to the country. Where we are able to work, we seek to employ South Sudanese health workers to support our efforts.”

For CDC South Sudan country director Rohit Chitale, the sole American direct hire, the staff’s commitment to the work and knowledge of the local context ensures continuity as country directors rotate in and out. “The FSNs have been trained well in Uganda and the U.K., and they could easily work elsewhere, yet are dedicated to supporting their country,” he says. “We are lucky to have had them for so long.”

By the same token, Chitale stresses the importance of outside support from PEPFAR and those it funds.

“Our continued presence and success in South Sudan is a testament to our partners here—partners like ICAP,” he says. “We are all committed to continuing this fight to bring health care to the people of South Sudan.”